Smash a melon, NOT my Boob!

Mammogram Risks

Women deserve more than marketing slogans. We deserve honest, evidence-based information. Informed consent is not just a formality. It’s a right. “Informed consent as a fundamental ethical standard in research and clinical practice.” The following are the required elements for documentation of the informed consent discussion: (1) the nature of the procedure, (2) the risks and benefits and the procedure, (3) reasonable alternatives, (4) risks and benefits of alternatives, and (5) assessment of the patient’s understanding of elements 1 through 4. Before you screen, make sure you’ve had a real conversation about the harms of mammography.

Don’t Just “Get Your Mammogram” — Get Informed.

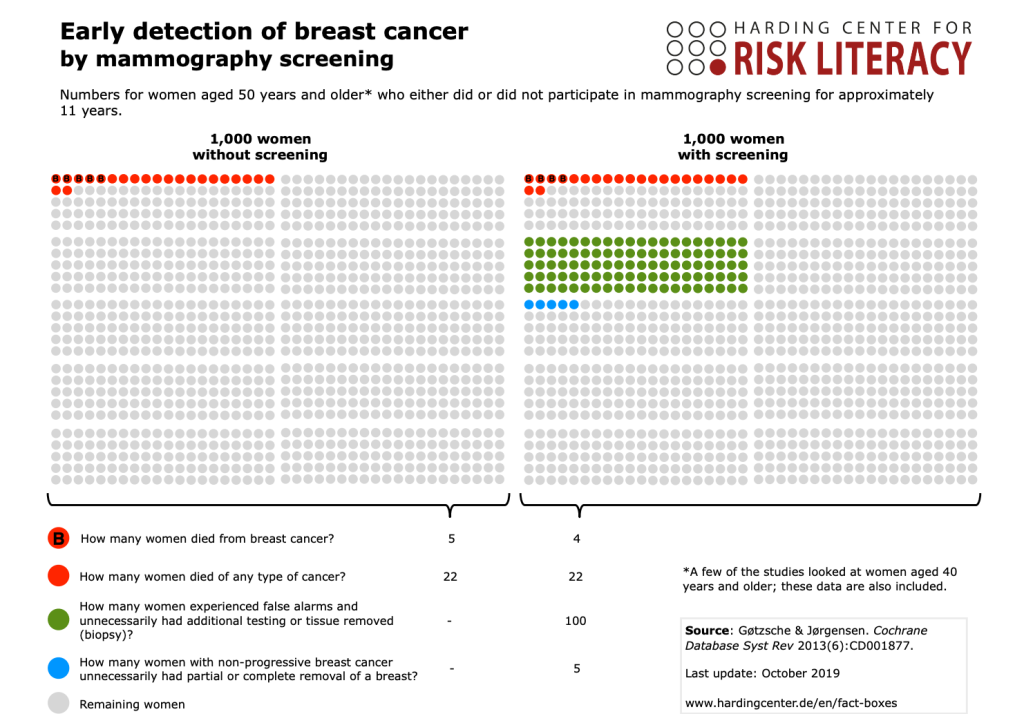

You’ve probably heard “Regular mammograms reduce breast cancer deaths by 20%” . Numerous national breast cancer organizations—including the American Cancer Society, American Society of Breast Surgeons, U.S. Preventitive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Prevent Cancer Foundation and many others —strongly advocate for regular mammography citing mortality benefits. Their education and outreach reinforce messaging such as “early detection saves lives,” often summarizing this as a 20% reduction in breast cancer mortality. That sounds impressive, right? But let’s break it down. This is one of the most misleading aspects of mammography promotion since the number refers to relative risk and not the actual number of lives saved.

When you hear “20% reduction,” it’s easy to assume that 20 out of 100 women will be saved. In reality, the numbers tell a very different story. For every 1,000 women screened regularly over 10 years, only 1 life is saved from breast cancer, see the graphic below. So yes, mammograms may help a small number—but at a cost that is rarely discussed.

Under-Diagnosis

Mammograms Miss Invasive Cancers

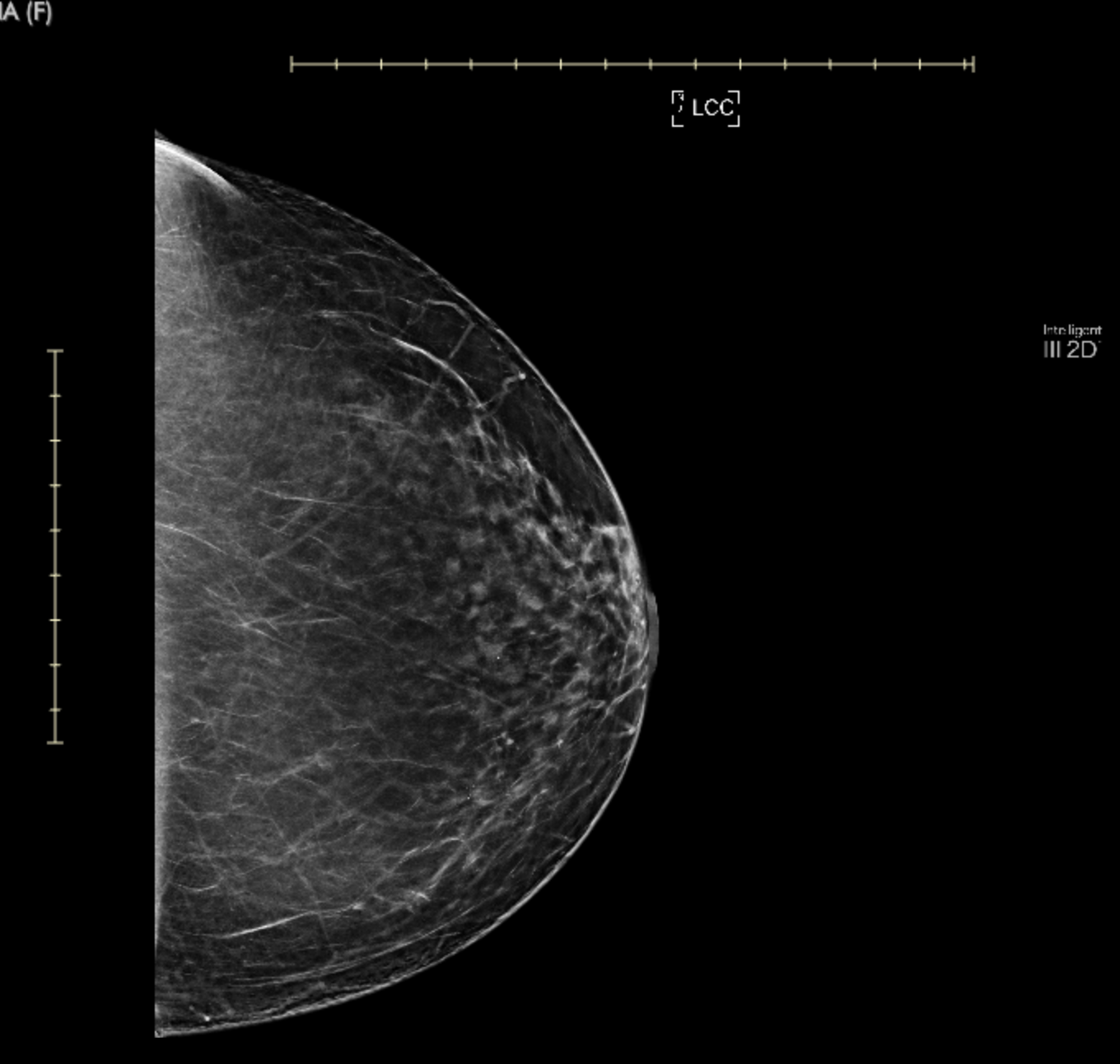

Did you know that mammography misses 40% or more of invasive cancers in women with dense breasts? Dense tissue and tumors both appear white on a mammogram, making it like “looking for a snowball in a snowstorm.” Increased density = decreased mammogram accuracy. Unfortunately, this also means increased radiation. Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), or 3D mammography, takes multiple X-ray images from different angles to create a layered, 3D-like image of the breast. It is aggressively marketed as an “improved” tool for women with dense breasts. But many women aren’t told the full story — particularly about increased radiation exposure and lack of proven benefit.

More than half of women have dense breasts. As of September 2024, women receiving mammograms in the US are officially notified whether or not they have “dense breasts.” While intended to improve transparency, this new requirement carries serious repercussions: psychological distress from a label that sounds alarming, confusion without a clear explanation, and, in many cases, women feel pressured into additional imaging such as 3D mammography, which exposes them to higher levels of radiation.

Over-Diagnosis

Over-diagnosis leads directly to over treatment

Overdiagnosis happens when a mammogram finds something that looks like cancer but would never have grown, spread, or threatened a woman’s life. The most common example is ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)—sometimes called stage 0 breast cancer.

DCIS is detected almost entirely through mammograms, not because it causes symptoms. The problem is that while mammography picks it up frequently, only about 5% of DCIS ever progresses to invasive breast cancer. This means the vast majority of women diagnosed with DCIS through screening undergo treatment for a “cancer” that may never have harmed them. By finding and aggressively treating lesions like DCIS, the medical system turns healthy women into patients and exposes them to risks without delivering clear survival benefit (Gøtzsche & Jørgensen).

Once something is found, most women feel they have no choice but to treat it—regardless of whether it’s dangerous or not. This can lead to unnecessary biopsies, lumpectomies, mastectomies, radiation, and chemotherapy for conditions that may never have progressed or become life-threatening.

Radiation Harm

Radiation Cause Serious Harm

Mammography is an X-ray test. Like any X-ray, it involves ionizing radiation and mechanical compression. X-rays were originally developed to look through dense bone, not soft tissue. This distinction matters, because imaging soft tissue like the breast requires different techniques: greater compression and often higher and repeated radiation exposures. Fat, glandular tissue, and connective tissue in the breast absorb X-rays poorly compared to bone. To overcome this, mammography uses lower-energy X-rays (around 20–30 keV range) to improve contrast between fat and glandular tissue. But this also means that more radiation is absorbed by breast tissue, which is more sensitive to radiation damage than bone. Radiation is cumulative and can cause cancer.

Compression Pain

Compression Cause Serious Harm

Mammography works by pressing the breast between two plates to flatten tissue so X-rays can capture clearer images. While this step is necessary for image quality, it often causes discomfort — in fact, most women report some degree of pain, and many describe it as moderate to severe. If there is already inflammation, a lump, or a recent biopsy, compression can worsen the situation. Though usually described as a “necessary discomfort,” the reality is that mammographic compression can cause real physical harm in addition to temporary pain.

Additionally, the size and density of the breast affect the amount of radiation and pain from compression.

Mental Harm

Dense Breast Notifications and Mammograms Affect Mental Health

Screening mammograms often detect “something suspicious” that turns out to be nothing. This leads to anxiety, extra testing, and invasive procedures that carry their own risks. False alarms and unnecessary diagnoses can cause long-lasting emotional distress, depression, and even PTSD-like symptoms.

Once a patient is told they have “cancer,” even if planned management is safe and non‑invasive, anxiety and distress tend to follow, regardless of whether they opt for surgery or monitoring. Similarly, when women are told they have dense breasts, they may experience heightened worry and uncertainty, even if the information does not necessarily indicate an increased immediate risk.

This emotional burden—rooted in the label itself—can strongly influence patients toward more aggressive treatment, even when their clinical risk is low.

Our Stories

Smash a melon, mot my boob!

Disclaimer

The information provided on Smash a Melon, NOT My Boob! is for educational and awareness purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. We are not medical professionals.

Always seek the advice of a qualified healthcare provider regarding any medical condition, screening decision, or treatment option.

Connect with us today and join our challenge!

Subscribe

Join the conversation

Help us smash the silence.